| Saturday Vigil | 6.00pm |

| Sunday |

8.00am 11.30am 7.00pm |

| Monday - Friday |

8.00am 10.30am |

| Saturday/Bank Holiday | 10.30am |

| Holy Day Masses |

Vigil 6.00pm 8.00am 10.30am 7.00pm |

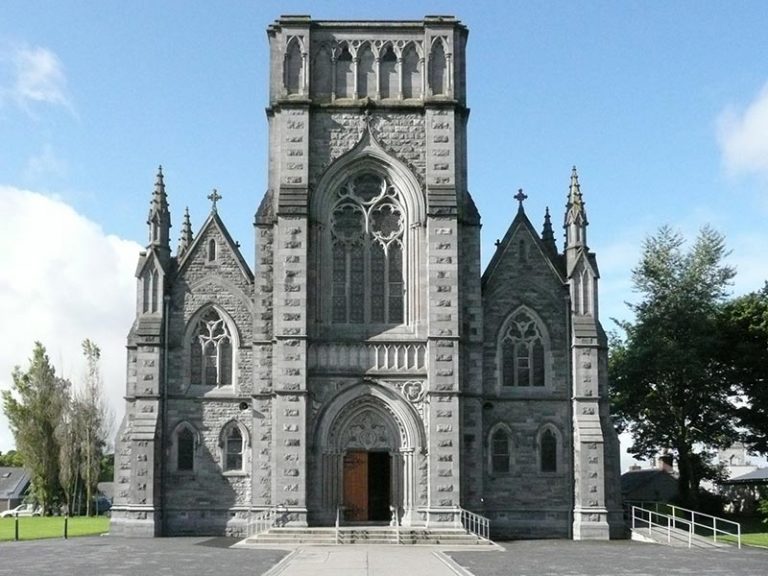

History of O’Loughlin Memorial Church of St John the Evangelist

The O’Loughlin Memorial church of St John was built between 1897 and 1908 but for nearly 800 years the people of the area have worshipped in a church dedicated to St John the Evangelist – the beloved disciple. First, Bishop Felix O’Dulany (1178-1202) and then in c1211 William Earl Marshall, the Norman lord who built Kilkenny Castle, endowed the Canons Regular of Saint Augustine, known as the ‘Brethren of the Hospital of St John the Evangelist’ with a site to the east beyond the bridge of Kilkenny. On the 27th December 1220 (feast day of Saint John), the first Mass was celebrated in the chapel of St John the Evangelist of Kilkenny. Ruins of this beautiful gothic church, once known as the ‘Lantern of Ireland’ still exist, and the bridge, street and parish have all maintained the name of Saint John’s or John’s. The Abbey/Priory church continued as the centre of worship, with varying fortunes until the reformation, when it was suppressed by Henry VIII in 1540. Except for a few periods during the seventeenth century when the Jesuits and Capuchins were established there, this church did not resume its religious aspect until 1817 when the Lady Chapel was re-roofed as a Protestant parish church, still in use today.

Henry VIII appointed the last prior of the Abbey, Richard Cantwell, as curate and chaplain of the Parochial church of St John the Evangelist, Kilkenny. Probably the church serving the Magdalen Hospital Maudlin Street, where the old graveyard is sited, was the one used. It was here the subsequent catholic churches of the parish were located until 1908. There are records of a Mass House, and later a chapel being repaired and rebuilt in 1796. The latter, a cross chapel, was taken down when a new stone church was built beside it in the popular revival gothic style, between 1840-47. This church, built with dressed limestone, had a narrow lancet side and end windows, a central tracery one of three-light, and a carved marble alter. It was closed for worship when the present church opened in 1908. In the 1950s it was taken down and the dressed stone used to build the Collier wing of St Kieran’s College. The short life of this quite impressive church of Saint John’s was due to the following circumstances.

O’Loughlin connection

A young man, Martin Laughlin/O’Loughlin, born c1833, from Castlewarren, a little village bordering Saint John’s parish, quite obviously had the spirit of adventure and the wish to travel and make his fortune. An attempt in his late teens to join the American gold rush failed, due to the ship he was travelling on going aground at Newfoundland. Returning to Kilkenny he was apprenticed to a biscuit maker, but later on hearing of gold finds in Australia he set out to try again. He was lucky, when he arrived in the area of Ballarat, Victoria, he made an early gold find. He invested in other mines and worked with varying fortune for about ten years. He then stuck a thick seam of gold, and the resulting mine flourished. Martin O’Loughlin, as a major shareholder prospered. He lived well, bought vast estates and took up horse racing as a hobby. All his ventures were successful, and he gave away large amounts of money to charity. A wealthy and religious man, he had expressed a wish in his will, before he died in 1894, that part of his estate be used to build a church in Australia or Ireland, in memory of the O’Loughlin family. His nephews Thomas and Martin O’Loughlin, the beneficiaries of his will, did just that. Thomas, the elder nephew was the one actively involved and he decided to build in Kilkenny. The family had by then purchased Sandfordscourt in Saint John’s parish, Kilkenny, and St John’s was the parish chosen. The spacious site selected, close to the existing church, was part of the Ormonde estate and it was presented free of all charges to the parish by the 3rd Marquis of Ormonde. The design of the architect William Hague was selected. The original contract for £19,750 was signed by contractor Stephen Lalor, with Michael Loughlin (the father), Thomas Loughlin and Rev. Patrick Aylward, Administrator Saint John’s. This probably included only the construction of the building, which was to be completed by 1899. The foundation stone was laid by the Bishop, Most Rev. Abraham Brownrigg on May 2nd 1897. The inscribed silver trowel used is still in the possession of the Lalor family. The Inscription reads:

Presented to The Most Rev. Dr Brownrigg, Bishop of Ossory, on the occasion

of his laying the Foundation Stone of the new church of St John’s, Kilkenny,

on the 2nd May 1897. Rev. Patrick Aylward , Administrator, Michaell Loughlin, Martin Loughlin, Thomas Loughlin, Donors. William Hague, Architect.

Stephen Lalor, Contractor.

William Hague’s sudden death from pneumonia in March 1899, and other problems left the contractor in serious financial difficulties. In July of 1899, surveyors P.&D. W. Morris had compiled an estimate that £12,154 16s 0d was needed to complete the contract. In May 1901 agreement and final payment of £2,500 ( total paid £15,650) was reached with Stephen Lalor, and the completion of the building advertised for tender. William H. Byrne, of 20 Suffolk Street, Dublin, had been appointed architect. Patrick Nolan, a contractor from Monaghan, who had worked on Saint Patrick’s church in Kilkenny, was chosen. Thomas O’Loughlin, who was back in Ireland at the time, signed the contract for the completion of the church on the 29th July 1901, and left for Australia the next day.

The work was to be carried out in accordance with the design of the late William Hague, in two sections, at a cost of £15,701. Bishop Brownrigg, though he did not sign the contract became Thomas O’ Loughlin’s representative locally, and took a very active part in all the subsequent decisions. There were some further delays, correspondence with Australia being slow. By 1906 further plans, such as those for the altar and furnishings were obtained. Thomas wished to supply everything himself for the church, and was kept informed of all details by Bishop Brownrigg. The Consecration and opening were planned for June 1908. Even the boundary wall, fine entrance gates and wall, and the laying out of the grounds were completed before the opening. On the 19th June from dawn to noon the consecration ceremony was conducted by Bishop Brownrigg. On Sunday 28th June His Eminence Cardinal Logue, with archbishops, bishops and many clergy officiated at the grand opening and the city officials, dignitaries and parishioners packed the church. Thomas O’Loughlin occupied a special seat in the sanctuary. The Freedom of the City was conferred on Thomas O’Loughlin as was the title, Knight of St Gregory the Great, by His Holiness Pope Pius X, before he returned to Australia. In 1911 Thomas returned to Kilkenny to marry Kathleen Murphy from Ballybur, County Kilkenny, in St John’s and both lived, prospered and died in Australia.

Characteristics

Saint John’s was built in the popular gothic style. The plan consists of the nave, sanctuary with an apse, two side aisles and side chapels and an organ gallery at the entrance end. There are six bays of column supported arcades separating the centre from the side aisles. Pinnacles, both outside and inside, the vaulted ceiling, and the decorative sculpture are notable features. The stone mullions and tracery of the windows have some echo of the original Saint John’s Abbey. The splendid mosaic floor shows the influence of the Gaelic revival. William Hague, who by this period had designed many churches, mixed conservatism with extravagance. As an employer’s wishes and funds have an influence on design, in St John’s Hagues’s artistic abilities had an opportunity to flourish. The church is built in a combination of rock-faced and ashlar-dressed Kilkenny limestone. On approaching the main entrance of the church, one is struck by the unusual flat top of the tower, height 74ft, which some consider has an unfinished appearance. Though a flat tower can be seen on some churches, as for example at St Edmundsbury Cathedral, Suffolk, in St John’s there was a designed steeple that was never erected. It is believed locally that this omission was possibly due to a deterioration in the ground conditions and fears that the stability of the building might be affected by the additional weight and, perhaps more realistically, that so much had already been spent on the church, the cost would be too much. Undoubtedly the planned steeple of 234ft would have been both very heavy and costly. The church measures approximately 130ft by 54ft inside. The interior enclosed porch was an added extra by William H. Byrne, during the construction of the church.

Exterior

The main entrance door is surrounded by four orders of polished Galway granite colonettes, 6in by 7ft at either side. The second order from the outside, of the overhead arch, is decorated with nineteen ball-flowers. The door is surmounted by a tympanum with a beautifully sculptured panel of an eagle, representing Saint John the EvangeliSt The spandrels of the arch include two monograms, SJ and SK, presumably for Saint John and Saint Kieran, (patron of the diocese). Spaces are filled in with decorative foliage in Portland stone which contrasts well with the darker limestone. Overhead there are two blind arcades and between them a four-light window with elaborate tracery and a moulded sill. The window’s hood moulding has sixteen carved crockets of about 12in by 12in by 9in, though from the ground these look much smaller. The buttresses that extend up both corners of the tower each terminate in a single arcade. These form part of the upper blind arcade. The tower is finished with a string course.

Either side of the tower the lean-to roof of the aisles are concealed by pointed gables. The ground floor of the aisles have two cusped one-light windows. Overhead, the hood moulding of a much larger three-light tracery window connects into the string course from over the lower blind arcade of the tower, which is continued across and around the buttresses, uniting the aisles with the tower façade. Crosses (about 3ft high) cap the gables which are recessed the depth of the buttress form the façade of the tower. The buttresses on the outer corner of the gables are finished by a little gable over two narrow blind arches and surmounted by a pinnacle. These attractive pinnacles, which have numerous carved crockets and ornate finials, were built by both contractors and are a feature of the church. A plinth of about 4ft forms the base of the building with three granite steps at the entrance extending around the tower buttresses. At the entrance door are two Kilkenny limestone holy-water fonts. Two small side railings were added to assist entrance in the late 1930s and blend in well, though different to the original McGloughlin iron work.

The sides of the church are similar, except on the left (facing the church) there is the sacristy and on the right a 1990’s ramp to the side entrance door, whose hand rails though strong, do not blend in with the earlier work. The side doors have four steps and a relieving arch of Bagnelstown granite. These relieving arches are unusual, as they are the only obvious granite in the building, apart from the steps. Over the door there is a two-light tracery window. The exteriors of the two recessed confessionals in the side aisles are quite ornate with small buttresses, pointed arches, polished granite piers and small slot openings. Between the confessionals a large buttress has, springing from it, a flying buttress which arches over the lean-to aisle roof and engages with the main structure. The main buttress itself is capped by a pitched roof niche (18in wide and 9in deep), with cusped arch-head and octagonal chamfered base which was probably intended for a statue. The aisle windows are single-light with a small amount of tracery and those of the clerestory are two-light with somewhat more tracery, all have hood moulding with carved bosses. At the roof edge there are dentil-type courses supporting the gutters at both levels. At the top of the nave at the base of the roof there are further ornate pinnacles. The roof of blue Bangor 28inch slates is capped by ornamental fire- clay red ridge tiles.

The sacristy is like a miniature gothic church attached to the top of the left aisle (from the front of the church). It is lit by two-light tracery windows. The plinth here and under the sanctuary is high enough to take a door and windows for lighting the basement area. Planned originally mostly for a heating and storage area, part of the basement area is now used for a variety of activities. The flight of granite steps at the front of the sacristy leads to the top of the aisle, to toilet facilities and to the sacristy. The pinnacles of nave and side chapel dwarf the chimney.

A new rear entrance to the church grounds was made from Maudlin Street in the 1980s, and in some ways this leads to the most attractive view of the church. The design of a sanctuary with an apse shows a continental influence as in England the straight end was more favoured. Each of the five-sided sections of the apse has a large single-light tracery window with hood moulding and bosses. A Latin inscribed memorial slab is inserted in the centre section which reads: ‘D. O. M. Ecclesia Sanct Joannis Evangeliste A. D. 1906 L. D. S.’ On this facade both aisles have three-light tracery windows with hood moulding and bosses. The point of each end gable and the apex of the apse are each crowned with a cross.

Interior

The interior of the church has a warm and joyful atmosphere. The combination of columns, vaulted ceiling, timber, decorative carving, with the colour and light are easier to see and experience in a picture or better still in a visit, than to describe. The vaulted groined plaster ceiling of the nave, sanctuary and side chapels are truly beautiful especially since they have been painted, in a warm pinkish brown colour. The crossings of the ceiling ribs are decorated with carved bosses. The ceiling ribs rise from colonettes of polished Galway granite, which are supported on carved Portland stone corbels. These corbels are carved with different designs and have each a symbol, Pope’s crossed keys and mitre. Bishop’s mitre, chalice, phoenix, the passion symbols, etc. picked out in gold. The pitch-pine lean-to ceilings of the aisles are supported on the nave side by arched timber struts, rising from carved corbels. The ceiling of Saint Patrick’s Church Kilkenny (1899), by the same architect and builder (Hague and Nolan) of panelled pitch-pine, arranged in herring-bone fashion is similar. There are other similarities, such as the patterned tiles and windows, though St Patrick’s is a simpler church and cost much less (£7,313 15s 4d).

The nave of the church has five open bays, a sixth bay is occupied by the organ loft carried on an arcade with the porch situated underneath it. The nave is separated from the aisles by an arcade whose pillars of clustered columns appear round, but are actually more square, made of four quadrants of half rounds, set on the diagonal. The octagonal plinth is surmounted by a round white marble base, which supports polished Galway granite column shafts about 10ft in height. The 18in round capitals are of Portland stone.

Sanctuary

The roof of the sanctuary is lower than the nave. There is an arcade of three smaller bays and the wider clerestory tracery windows are single-light. The same materials form the round columns of this arcade and here the capitals are richly carved. The main sanctuary arch, which is a composite pier, includes as well as three tall slender polished granite columns on the inner arch, a mixture of both types of columns from the arcades of nave and sanctuary. About the 1940s a crucifix, nearly 9ft. high was added to the right hand column of the sanctuary arch. The work to mount it was carried out by Dan Brennan, monumental sculptor. Ball flowers decorate the arches of Bath stone separating the side chapels from the aisles.

The high altar

There is a family tradition that the original design for the high altar was a simple table altar with the decoration being supplied by the separate ornate reredos and that this was changed by Bishop Brownrigg’s wishes. The design used for the altar was agreed after Bishop Brownrigg had consulted Thomas O’Loughlin in 1906. He sent two designs, saying “one is drawn by Mr. Byrne from instructions I gave him and would cost about £1,250, the other is the picture from an Altar in the Dominican Church, Newry, and cost £1,184” and later adds in the letter “I think Mr. Byrne’s design is in every way more suitable to St John’s church than the Newry Altar.” Thomas O’ Loughlin, that generous man, replied “Seeing that there is only £66 difference between the two designs or even is there was more, by all means take the £1,250 design, as your Lordship and Mr. Byrne have agreed it is the most suitable.”

The altar table is now free standing, though prior to its relocation to comply with current liturgical practices in the 1980s, it formed a single unit with the posterior part of the altar that holds the tabernacle. This relocation was carefully carried out by Pat McDonald, Dunbell, and Matt Gargan, Kilkenny. The central panel sculpted in Carrara marble depicts the Last Supper and modern concealed lighting adds to the sculpture’s beauty. On either side there are recessed panels containing Carrara marble angels in adoration. There are some similarities to the high altar in Maynooth designed by William Hague. The reredos, separate from the altar, is formed round the walls of the apse and executed in Caen stone. In the angles clusters of coloured marble columns support canopied niches and pinnacles, in which are placed figures of saints. Between these canopies and ornate pinnacles are five panels with tracery heads crowned with angels. Four beautifully carved Caen stone panels depict (right to left): St John and St Peter at the gate of the Temple; the petition of the mother of St John; St John taking the Virgin Mother home; and the calling of St John and St James.

The nets of the fishermen, somewhat crumpled, look as if one could take them up to shake and fold them. The centre panel, at the back, was left without a pictured sculpture as the high tabernacle section of the altar conceals it. On the right of the altar the marble piscina is inserted under one of the panels.

The tabernacle features double columns of Mexican onyx and is richly moulded and crocketed. The hammered brass door has a chased design. Over the tabernacle a groined vaulted canopy is supported on four red marble columns and inside there is a pedestal for a crucifix and a lovely dove in flight. A second open designed canopy, surmounts the first and the whole terminates in a pinnacle and cross. During the 1980s renovations the pulpit was removed, but parts were re-used, providing a marble chair and two front-pieces, one for underneath the tabernacle and the other for the front of the ambo. George Smyth, 196 Great Brunswick Street, Dublin, was the sculptor of the high altar and the reredos. The contract for his work was £1,180 (£100 of this for the sculpture of The Last Supper). Money value has changed greatly, but by any reckoning he has left a splendid legacy in his work in the church. The pediment of Saint Mel’s Cathedral, Longford, and the transept altars in Cobh Cathedral, Cork, are other examples of his work.

The side chapels

The Sicilian marble altars and pedestals have coloured foreign marble shafts. The fronts are moulded and beautifully carved with monograms in the central panels. The tabernacles have richly ornamented hammered brass doors. The reredos of carved Caen stone have recesses for the statues, on the right, the Blessed Virgin, (the Immaculate Conception) and the left, Saint Joseph. The cartoons for the statues had to be submitted for the approval of Most Rev. Dr. Brownrigg. The altars were executed by Early & Co., and the contract price was £420 0s 0d. The architect disallowed £20 of this because of the quality of some of the marble used, though the altars look extremely well and there are no obvious flaws. The pulpit was made by Edmund Sharp, sculptor, 42 Great Brunswick Street, Dublin, and the drawings for the panels were by Messrs. Mayer & Co. Edmund Sharp was also responsible for the baptismal font and for the two items he was paid £303. The richly carved octagonal baptismal font supported on columns of red Skyros and Siena marble is now in front of the side altar to Our Lady. The altars in Saint Columb’s Catholic Cathedral, Derry, when it was extended in 1903, are other works by Edmund Sharp. The 1980s renovations in St John’s also involved the removal of the arcaded carved Sicilian marble altar rails and the hammered brass gates from between the nave and sanctuary. Parts of them were used to form seats and a stand. However, the altar rails have been retained in the side aisles and the local sculptor and contractor Edward O’Shea is credited with this work.

The floor of the sanctuary and side chapels

One of the most interesting decorative features of the church is the magnificent mosaic floor which extends across the sanctuary area. The influence here of the Gaelic/Celtic revival and the arts and craft movement are very evident. The free flowing interlacing, animal heads and curves incorporating the different symbols are quite stunning and would uplift anyone’s spirit. The centre piece of the pelican feeding her young as a symbol of Christ, is surrounded by angels and the symbolic representation of the four evangelists. Grapes and wheat are stylized in other sections and in nearly all areas the colour and condition remains excellent. The sanctuary steps are of polished white Sicilian marble. The mosaic paving was part of William Hague’s design. The work was carried out under William H. Byrne, architect, and Patrick Nolan, builder, to the design of Ludwig Oppenheimer and is certainly a credit to both of the architects, the designer, the builder and the “specially skilled tilers and pavement fixers” who were designated in the contract to do the work. The centre and side aisle passages in the church have patterned ceramic floor tiling, and the remainder of the floor is completed in pitch pine wood block, set in a herring bone fashion, and both continue to look and wear extremely well. The woodwork by Timothy and John D’Arcy, Kilkenny, for the 92 benches, four kneeling benches, vesting table and three presses, cost £637. All made from pitch-pine, they have beautiful moulded and rounded edges and show a great variation in their carved ends. Arcaded moulded pitch-pine barriers about 2ft 6in high separate the nave and aisles and parallel the heating radiators. The barriers’ central posts, originally taller, were designed to carry the brass standard for the gas lighting. They are now crowned with rounded caps, about 7in high, with domed tops which look machine-turned. While the reduced height improves the view from the side aisles the design and workmanship contrasts with the original hand-crafted woodwork.

Other fittings

For the Stations of the Cross Mayer & Co. were paid £252, and while these might not be the type which are most favoured at present, they fit in well with the general interior of the church. William H. Byrne was responsible for the organ gallery, which is fronted by a pitch-pine arcaded balustrade with a carved beam underneath. The original organ was built by John White of Dublin and rebuilt later by Alex Chestnutt of Waterford, who was responsible for the present twin organ cases, leaving the centre of the gallery open for a clear view of the four-light window. Following a recent restoration by Kenneth Jones & Associates, it is now suitable for recitals which are held there occasionally.

The enclosed porch, has a pitch-pine screen with leaded lights extending up to the ceiling. The upper portion has clear glass, while in the lower part, where there are three sets of doors, the glass is coloured. Similar paired doors at the end of the aisles, lead to the external side doors and a confessional room. The doors have brass protection bars, and great credit is due that all have been retained, as the richly coloured cathedral glass and dark wood are very beautiful and add to the symmetry of the church. A grandfather clock has stood in the sanctuary at the sacristy door for many years. The mahogany case has beautiful inlay and fretwork. The movement is two-train and the break-arch dial has a silver chapter ring on a brass face and spandrels. The roman numerals are of wax inlay. Supplied in 1914 by Hopkins & Hopkins, Dublin, it cost £14 16s 6d. The brass fittings of the church, the gas fittings and the metal work of baptistery and entrance railings etc., are the work of I & C McGloughlin Ltd. of Great Brunswick Street, Dublin. Their work has survived at the entrance gates, where their signature is on the locks. McGloughlins were specialists in art brass and iron work and other examples of their work are in SS Augustine and John, Thomas Street, Dublin.

In the apse above the reredos, the three very colourful stained glass windows were supplied by Mayer of Munich, their name can be seen on the lower right side of the right hand window. They are not detailed in the original recorded costing so were either included within the overall contract charge or were installed sometime later. They add to the beauty and colour of the church and depict a vision of heaven with God entrusting the future of the world to the Lamb, as portrayed in the Book of Revelation, chapters 4 and 5. A replacement window in St Mary’s Cathedral (for one that had blown in) was also by Mayer and cost £300 sometime after 1877. All the remaining windows in St John’s have leaded coloured glass, individually in a simple design, but overall they give a unity and, with so much richness in other details, perhaps a simplicity to the church.

In the porch an inscribed brass memorial tablet by Hardman reads:

The O’Loughlin family of Sandfordscourt in this Parish, Michael and Margaret parents, Thomas and Martin children, founded, built and furnished in all details this spacious and beautiful Church unto the honour and glory of God under the invocation of Saint John the Apostle, Patron of this Parish, at a cost of £40,000 in the first place as a mark of their own faith and devotion to God, and in the second place as a lasting memorial of their gratitude to Martin O’Loughlin, brother of the above Michael, who died in Australia leaving them a large fortune which he had made there. To all of whom, whether living or dead, may God be propitious and merciful. This Church was solemnly consecrated to God by the Most Rev. Abraham Brownrigg, Bishop of Ossory on Sunday, June 28th 1908.

William Hague

William Hague (1836-1899) was born in Cavan town, eldest son of William And Catherine Hague. He attended St Augustine’s Academy, Cavan, between 1847 and 1853 after which he pursued his architectural studies in Dublin. He started his Dublin practice at 175 Great Brunswick Street in 1861. In 1862 he was elected a fellow of the R.I.A.I. but had at that time already designed a number of buildings, including a Methodist church in Cavan in 1859 and a Catholic parish church in Ballybay, Co. Monaghan. He established a flourishing practice, specialising in church design and renovation. Hague was heavily influenced in his early work by J.J. McCarthy, and by the gothic revival movement that took its inspiration from the buildings of the later middle age especially the soaring spires of the cathedrals of continental Europe.

Over 100 works either built or remodelled by Hague are listed by Ciaran Parker, nearly half of them are churches. Hague’s working life coincided with the wave of Catholic church and convent building, but he also designed for other religious persuasions and some secular buildings. At Hilton Park, Clones, he remodelled both the exterior and interior for John Madden. Omagh Catholic church was completed in 1899, and there Hague’s facade, which had twin towers with spires, was completed. Letterkenny Catholic Cathedral, the last of the gothic revival Cathedrals to be built, would probably be considered Hague’s ultimate achievement and certainly exhibits his interest in decorative spires and pinnacles. The twin-pinnacled flying buttresses articulate with the facade and rise into four belfries in their own right. The interior of Letterkenny is lavishly decorated, and includes mosaic, frescoes and sculptures. It was not finished at Hague’s death and was completed by Thomas F. McNamara who had been his managing assistant, and with whom his widow, Anne, formed a partnership. That partnership, Hague & McNamara, practised until at least 1907. Both Hague and Oppenheimer were involved in SS Augustine & John, Thomas Street, Dublin, Hague with the apse, and Oppenheimer with the mosaic. Similarly in St Patrick’s College, Maynooth, where Hague designed the soaring tower and spire, the mosaics are by Ludwig Oppenheimer, so perhaps these contacts influenced the architect’s choice of mosaic designer for St John’s. In Maynooth Hague completed J.J. McCarthy’s interior, though his spire was built posthumously.

St John’s Kilkenny, while perhaps not William Hague’s finest achievement, is undoubtedly one of his masterpieces. With William H. Byrne’s additions and the workmanship of all involved with the construction, it is undoubtedly a fine building. The excellent condition in which the church and grounds are kept, are a credit to all involved, and a fitting tribute to the O’Loughlin family who very generously built it. It is indeed a church that is a fitting and inspiring place to worship and honour God.

St John's Parish, Kilkenny, Ireland

St John's Parish, Kilkenny, Ireland